Cumberland Council has now replaced the previous Cumbria County Council and 3 District Councils. The content on this website is still relevant including documents that may include the old county council logo. Find out about the council changes

Please update any cumbria.gov.uk browser shortcuts you may have to the new site pages as needed

Life at home

Bramwell (Bram) Longstaffe was twice elected Mayor of the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness, in 1934-1935 and 1935-1936, and a primary school in Barrow is named after him.

During the First World War Bram Longstaffe was the local Branch Secretary of the Independent Labour Party and of the No Conscription Fellowship. He was jailed as a non-cooperative conscientious objector and in addition was sentenced to a month's hard labour in September 1916 on the trumped-up charge that he had used language likely to cause disaffection among the civilian population, contrary to the Defence of the Realm regulations. The Chief Constable wrote personally to the Watch Committee to ensure that Longstaffe's appeal against this sentence was dismissed at the following Quarter Sessions in Lancaster. At the instigation of the local Conservative Party he was struck from the list of electors in 1919 but despite this he was still able to stand for the Borough Council and was duly elected.

On his death at the young age of 57, the presiding magistrate said in tribute that Bram Longstaffe was a man who 'at the cost of considerable suffering, pain, and anxiety, and apparently at the sacrifice of all future prospects, had on occasion taken stands which brought him anything but popularity.'

On Bram Longstaffe's gravestone in Barrow Cemetery are inscribed these lines by Ralph Chaplin:

Mourn not the dead that in the cool earth lie,

Dust unto dust,

The calm sweet earth who mothers all who die,

As all men must,

But rather mourn the apathetic throng,

The cowed and meek,

Who see the world's great anguish and its wrong,

And dare not speak.

This small mounted black and white photograph of Bramwell Longstaffe by Storey is now kept at the Dock Museum, Barrow-in-Furness.

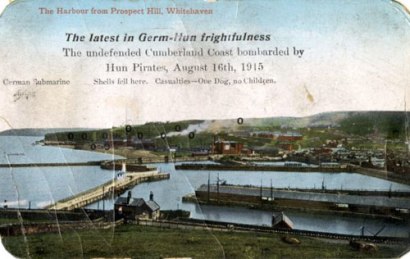

Germ-Hun frightfulness.

16.08.1915; 8:35pm. Official Report from the British Press Bureau - A German submarine fired several shells at Parton, Harrington, and Whitehaven, between 4:30a.m. and 5:20a.m. today, but no material damage was caused. A few shells hit the railway embankment north of Parton, but the train service was only slightly delayed. Fires were caused at Whitehaven and Harrington, which were soon extinguished. No casualties have been reported.

The Germans reported things differently announcing 'On August 16th, one of our submarines [U-24 commanded by Rudolf Schneider] shelled the Benzol and Benzol storage tanks, as well as the coke ovens attached to them, at Harrington on the Irish Sea. The works blew up, throwing up high flames.' This wasn't quite wishful thinking as one of the shells had ignited a drum of Benzol and the deliberate venting of flammable gas gave the impression of a destructive hit.

An investigation later found that the bombardment from the submarine lasted about 25 minutes; some fifty-five shells having been fired. The damage caused was valued at just under £800 and production at the works halted for four days.

A local poet wrote

His vessels came, they got no fish

They left behind no weepers,

His gallant charge had one result,

They broke some railway sleepers

A post card produced at the time was entitled The Latest in Germ-Hun frightfulness. The undefended Cumberland coast bombarded by German Pirates August 16th 1915…Casualties one dog - no children [See opposite illus]

A local Cumberland newspaper was equally dismissive of the attack and of the threat of submarines …..it was a complete failure. Not a single baby was killed, and the damage wrought by the shells was inconsiderable. Some 140 years have elapsed since last Whitehaven was subjected to bombardment by Paul Jones, and the fact that the German submarines should now be employed for such a purpose is a clear indication of their failure to perform the more important services for which they were specially built. This too was wishful thinking. From 1914 - 1918, 274 German U-boats sank 6,596 ships and their blockade of Britain was nearly successful. Between February and April 1917 U-boats sank more than 500 merchant ships. The introduction of the convoy system helped to reduce losses.

Belgian Refugees

by Denis Perriam

At the outbreak of war, Belgian refugees arrived in Britain in such numbers that it was necessary to find home for a quarter of a million men, women and children, the largest influx of political refugees in British history. Carlisle was expected to take 300. By September 1914 some refugees had already arrived in the city, but it was not until October that a Carlisle Relief Fund was formed. They were immediately offered Rickerby House as a reception centre by Mason Scott. It took time to prepare but early in November a house-warming was held at Rickerby where rooms had been made for 80 refugees. Meanwhile, other houses in the city were acquired on loan and citizens loaned furniture.

On 26 November 1914, the largest contingent of 44 refugees arrived at the station and were taken to Rickerby House, the Carlisle Journal reporting that each "wore labels on their breasts and that on the whole they were people of the better middle class."

Offers of employment came in December as the number of Belgians continued to rise. There were 49 refugees at Rickerby House on 3 December when they were visited by Sir John Barran MP.

A welcome letter in French appeared in the Journal on 11 December, addressed to the refugees at Rickerby.

A large number of well-wishers called at Rickerby to give their regards and the refugees were given a Christmas party at the Crown and Mitre Hotel.

Belgian children attended Carlisle schools and, to help in understanding their predicament, city school children were asked in February 1915 to imagine they were Belgian and write an essay on their experiences. Alexander Reid of Harraby wrote: "I am a little Belgian boy and our country is laid waste by the Hun." The Rev G S Kennedy made an application to the city in February 1915, to wave the electricity bill for 11 Chatsworth Square as there "were a number of Belgian refugees resident" and his request was granted.

In July 1915 one of the girls married a Belgian soldier who had been given leave from the trenches and the reception was held at Rickerby House. But not all Belgian women were treated kindly; two who gave their occupation as acrobatic musicians of no fixed abode had been living in a caravan at Blackhall, but were sent to the gaol for theft in August.

One family of Belgians settled in a house in Water Street, provided by the parishioners of St. Stephen's Church. However, they proved untidy and ungrateful, the father refusing to work. Unaware of these reasons for their eventual eviction, parishioners stoned the vicar in October, when they opposed their removal.

News came that month of the intended closure of Rickerby House. It had served its purpose as all the inmates were now re-housed and there were no new refugees. There were few further reports on the refugees, but in November 1916, there were vague complaints of idleness amongst those in Carlisle. At the AGM of the relief committee, it was stated that 70 were then on the register. The committee again met in April 1918 to announce that their funds were exhausted.

A Belgian inspector had visited the 61 refugees remaining in the city and wrote to the secretary of the relief committee: "The handsome accommodation you were fortunate enough to secure at so small a cost has no doubt further contributed to make your Belgians the happy and contented people they are." He added, "I was very impressed to see those who can, had started some kind of work."

Those who had done most on the relief committee were honoured by the King of the Belgians in July 1918, the medal citation reading, "in recognition of the kind held and valuable assistance personally given to the Belgian refugees during the war."

At a ceremony at the Town Hall in February 1919, the refugees presented a marble plaque in gratitude for Carlisle's hospitality, before they left.

All of the local refugees were to leave on the same train, joining at different stations. There was a large crowd to see those off at Carlisle Station on 27 March. The Times stated in April that many repatriated Belgians were applying for passports to revisit Britain. Two Belgian priests returned to Carlisle in 1969 and were pictured on the front page of the Cumberland News. Father Gerard and Arthur Van Maele had spent the war at St. Joseph's Home at Botcherby, with their mother and two sisters. The reason they had chosen to come to Carlisle as refugees was because their aunt, Sister Arsena, was one of the Little Sisters of the Poor at the Home. Father Gerard had fond memories as a pupil at Carlisle Grammar School and his employment at Carr's Biscuit Works from November 1916 to April 1918.